A Rededication That Took Dedication

by Jeremy Rothman | November 2025On June 8, 2024, I stood alongside fellow Philadelphians sharing in the immense pride of the moment. While it seems fitting that Marian Anderson’s name would now grace a concert hall in her hometown, it was not an obvious thing to do even 30 years after her death.

In a historically Eurocentric art form, renaming an orchestra hall for an African American woman could have elicited a justifiable sigh or facepalm. But The Philadelphia Orchestra had worked for years to build trust — through sustained partnership, engagement, and artistry — to arrive at this transformative moment.

In a historically Eurocentric art form, renaming an orchestra hall for an African American woman could have elicited a justifiable sigh or facepalm. But The Philadelphia Orchestra had worked for years to build trust — through sustained partnership, engagement, and artistry — to arrive at this transformative moment.

Marian Anderson grew up only a few blocks from the eponymous concert hall that now bears her name. From the stage door, I can almost see the low-rise brick building down the street that once housed the Philadelphia Musical Academy—the long-defunct school that refused her admission as a young Black girl. So it was Anderson’s determination and her extraordinary mezzo-soprano voice that carried her to the greatest stages of the world, including frequent performances and recordings with The Philadelphia Orchestra.

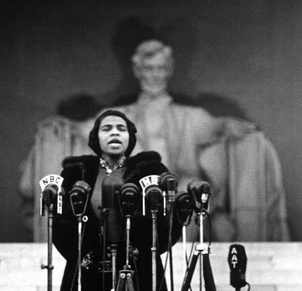

Anderson was the first African American to sing a starring role at the Metropolitan Opera. In 1939, when she was denied from performing at the 3,000-seat Constitution Hall because of her race, she sang instead from the white marbled steps of the Lincoln Memorial before an audience of 75,000.

Her rich, alto voice was equally matched by her powerful presence as a civil rights pioneer.

Her rich, alto voice was equally matched by her powerful presence as a civil rights pioneer.

Marian Anderson Hall, home to The Philadelphia Orchestra, had been named Verizon Hall since the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts opened in 2001. When it was rededicated, it became the only major orchestral concert venue in the world to be named for her, or probably for any woman of color for that matter. This was a major milestone for The Philadelphia Orchestra and for the often-cloistered world of classical music.

Historically, The Philadelphia Orchestra had at least some track-record of elevating African American composers and performers. For example, under Leopold Stokowski, The Philadelphia Orchestra’s statuesque Music Director of Fantasia fame, they premiered William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony in 1934 and William Grant Still’s Symphony No. 2, “Song of a New Race,” in 1937. Later in the 20th century, artists such as composer George Walker and pianist André Watts found an early and prominent place on stage with The Philadelphians. However, these efforts fell far short of being truly representative, even by classical music’s paltry standards.

Bold New Programming

When Yannick Nézet-Séguin became just the eighth Music Director in the Orchestra's century-plus history in 2012, there was renewed commitment from the outset. The Philadelphia Orcheatra was going to champion historically overlooked composers while commissioning and performing new works by an increasingly diverse array of living artists.

The Philadelphia Orchestra also started to engage in deeper, more meaningful residencies that immersed artists in Philadelphia’s unique culture. One key example, I invited Hannibal Lokumbe to be a multi-year composer-in-residence during which time he served as a critical bridge to many overlooked corners of the city. Hannibal is a polymath — a magnanimous, almost spiritual figure, full of generosity. He is an accomplished jazz trumpet player, composer, and poet who is outlandishly warm to people from all walks of life. He always greets me with the warmest hugs and is prone to texting me poems at odd hours of the night.

During one of his many residency visits to Philadelphia, I accompanied Hannibal and a string quartet of Orchestra musicians on a visit to a Philadelphia detention center in Holmesburg. Holmesburg is a bifurcated neighborhood wedged between eight lanes of I-95 and a swampy shore of the Delaware River.

Oh, and it is home to the city’s largest prison. The musicians played for about 50 incarcerated men in matching denim jumpers, several of whom were moved to tears by what they heard.

Oh, and it is home to the city’s largest prison. The musicians played for about 50 incarcerated men in matching denim jumpers, several of whom were moved to tears by what they heard.

In a later visit to Philadelphia, Hannibal assembled multi-denominational audiences for performances at the Museum of African-American History and the National Museum of American Jewish History. Another time he led an emotionally uplifting “walk for peace” through Old City Philadelphia that concluded with a concert at Mother Bethel AME Church — the oldest congregation of its kind in America. By the time Hannibal’s hourlong oratorio was premiered by The Philadelphia Orchestra at the culmination of his residency in 2017, I sat among three sold out houses, full of energized acolytes, that turned out to hear it.

Another critical moment in the Orchestra’s “Journey to Marian Anderson Hall” came in January 2019, when Yannick conducted the music of Florence Price for the first time. Price was the first African American woman to have her work performed by a major U.S. orchestra in 1933, yet whose music had been largely set aside for decades (including by The Philadelphia Orchestra who had shunned her music completely). After performing a bustling movement of her Symphony No. 1 at the Orchestra’s annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Tribute Concert at Girard College—a site itself central to Philadelphia’s civil rights history—Yannick said to me, “We are going to perform all of her symphonies on our subscription concerts beginning next season.” He and I then set out to aggressively lobby Deutsche Grammophon, the most prominent record label in Classical music that had just signed him to an exclusive contract, to release a complete recording cycle of her symphonies and concertos. The first album, featuring Price’s Symphonies Nos. 1 and 3, earned The Philadelphia Orchestra its first-ever Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance. It was about damned time, for both Price and The Philadelphia Orchestra.

Yannick and the Orchestra have since turned a focus to other overlooked African American composers including Still, Dawson and Margaret Bonds, through repeated performances, touring, and recordings.

A commitment to living composers has been equally prioritized. Gabriela Lena Frank accepted my invitation to compose a world premiere for Yannick’s debut concerts as Music Director in September 2012. And the Orchestra’s first live post-pandemic performance at Carnegie Hall in October 2021 opened with Valerie Coleman’s Seven O’Clock Shout, a work I encouraged and commissioned her to compose at the height of the pandemic lockdowns.

Going All In for Our City

Meanwhile, I and my education team ensured that the Orchestra’s off-stage work continued to redefine its relationship to its city. The Philadelphia Orchestra invested meaningfully in music education and community partnerships. A daily instrumental music program launched at KIPP West Philadelphia has now served hundreds of students that might not have otherwise ever picked up a trombone or bassoon. Fellowships have supported dozens of talented School District of Philadelphia musicians in advancing to top conservatories from Indiana to London. The Kimmel Center stages have become home to an annual festival for 400 public school instrumentalists, with their parents and friends cheering them on from the seats. Orchestra musicians regularly performed in community centers and children’s hospitals. Yannick conducted youth ensembles. And a weekly music therapy program took root at a converted church across the street from the Kimmel Center that provides services to the neighborhood’s homeless population.

A Case for Support

This artistic and community-based transformation required strong philanthropic investment. Few people outside the orchestra world realize that these ensembles survive mostly on philanthropy and endowments. Ticket sales only cover a fraction of an orchestra's costs. These century-old non-profits, that employ more than a hundred highly skilled fulltime musicians, have an increasingly greater reliance on contributed revenue and endowment income to support the orchestra’s artistry. Generally speaking, roughly one third of an orchestra’s expenses are covered by ticket sales — a percentage that grows smaller every year. Following the Orchestra’s controversial 2011 Chapter 11 financial restructuring, donors rallied behind a bold new artistic vision—supporting a decade of ambitious programming, collaborations, touring, and civic work. More than $300 million in contributed support was raised as a result. This was a clear endorsement of the Orchestra’s values and direction — shattering the traditional views of classical music.

Two extraordinary gifts were pivotal: a $50 million anonymous endowment gift, and a $25 million gift from longtime arts patrons Richard Worley and Leslie Miller to rename the hall. Rich and Leslie selflessly declined to have their own names on the building. Instead, they chose for the hall to be named for Marian Anderson.

On June 8, 2024, before civic leaders and Philadelphians of every stripe, Yannick pulled the rope on a purple drape and a new sign was revealed:

MARIAN ANDERSON HALL

HOME OF THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA

HOME OF THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA

A moment that could have been met with a collective shrug was instead met with cheers of pride for Philadelphia’s own.

Today, Marian Ansderson Hall stands as a beacon for the city, affirming that the arts belong to everyone. Reaching that day required the same authenticity, perseverance, and artistic excellence that defined Marian Anderson herself. And it was a clear demonstration of the power within us all to transform ourselves.